Happy danglers. Sandy Corner Rest Stop, Ayr. © JPM, 2022.

Probably more useful as candles than as food, at least in my experience!

Names

Candlenut trees hail from the genus Aleurites (A.), Australia being home to two notable species. Otherwise known as Indian walnut, carie nut and varnish tree, A. moluccanus is by far the most common of these. Older sources might still utilise the former nomenclature, A. moluccana (Willdenow, 1805) or Linnaeus's 1753 Jatropha moluccana. The other relatively common candlenut found in Australia is A. rockinghamensis. There is one A. fordii growing in the Anderson Gardens in Townsville and possibly others elsewhere.

Candlenut has many close relatives that grow across Asia and the Pacific including deciduous varieties from genus Vernicia which are common in China. These species will not be otherwise covered here, but note the caution on toxic look-alikes below.

Habitat and Range

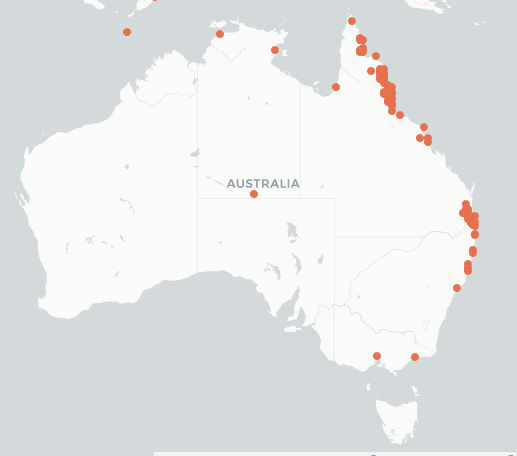

Candlenuts are a tropical and subtropical tree by nature, preferring rich, moist soil in rain forests and gallery forests near the coast all across the Pacific. They are especially prolific in Indonesia, Timor, Malaysia, Philippines, India, China and the African east coast. Candlenuts were introduced to most Pacific islands by island-hopping seafarers in bygone millennia, and are an important ceremonial item in Hawaii. In Australia's northern Queensland, it can be found up to 800m in elevation. Candlenut is one of the first reoccupiers of cleared or broken ground, such as fire trails, agricultural land or cyclone-damaged areas. It grows extremely fast.

In Australia, candlenuts are mostly limited to the north Queensland coast, mostly between Mackay and Cape York, with some isolated pockets also growing in South-east Queensland and northern New South Wales.

Identification

Key Identifying Features

Streaky white-gray trunk/bark, often with splotches of algae, moss or lichen.

Leaves are large (15-30 cm) and can resemble white fig (Ficus virens) with prominent veins, or exhibit 3-5 lobes similar to maple, or be heart-shaped.

Leaves have two round glands near the upper side of the stem joint

Young leaves have fine, white hair resembling a dusting of flour or icing sugar

Five-petaled, white flowers occur in inflorescences of 30-50

Fruit resemble walnuts, often with visible segmentation lines

Fruit falls from the tree when ripe, dries out and turns brown or black

Fruit contains one insanely hard shell

Once cracked, the shell contains one white, oily kernel (up to 65% oil).

Kernels will burn readily, lasting about 15 minutes and providing candle-grade illumination

Look for stout, whitish trees with streaky bark, often with splotches of algae, moss or lichen on the trunk. Rain may cause the colour to shift to brown. Mature candlenut trees generally have a large profile, being 15-30 m in height. Their lateral branches droop down and hook back up again near the tips (see header image above). Immature trees are easier to identify from their foliage.

Figure 2. A good example of the whitish, streaky trunk bark of A. rockinghamensis covered in splotches of lichen. Atlas of Living Australia. © Tim, 2021.

Figure 3. Rain-soaked trunk of A. rockinghamensis. Atlas of Living Australia. © R. Cumming, 2019.

Figure 4. Moss-covered trunks of A. moluccanus. Atlas of Living Australia. © M. Fagg, 2012.

Candlenut leaves can vary significantly, particularly between young and old trees. Look for the two bulbous glands at the leaf-stem joint for certain identification. New growth is often covered in a white 'dusting' of fine hairs resembling sprinkled flour; this also gives the trees a silver sheen in spring, another key feature. The leaves are prominently veined, usually with 3-7 lobes but some species can resemble white fig (Ficus virens), covered in part 16 of this series. Unlike white fig, candlenut leaves have a papery (rather than leathery) texture.

Figure 5. Mature candlenut leaves. This A. moluccanus tree did not exhibit lobes, making it resemble white fig (Ficus virens). Sandy Corner Rest Stop, Ayr. © JPM, 2022.

Figure 6. An example of the leaf glands, centre, on an A. rockinghamensis. Atlas of Living Australia. © S. Fitzgerald, 2022.

Figure 7. Young foliage exhibiting it's 'flour' dusting. Wikipedia. © Geographer, 2012.

Figure 8. Lobed young foliage of an A. moluccanus. Atlas of Living Australia. © B. Shevaun, 2020.

Figure 9. Example of the slightly lobed but overall 'heart' shape of an A. moluccanus. Atlas of Living Australia. © R. Chapman, 2007.

Figure 10. Example of the serrated, heart-shaped foliage of A. fordii. Atlas of Living Australia. © G. Cocks, 2013.

Flowers are five-petaled, white with no prominent anthers or pistil. They emerge on a stem (inflorensence) of 30-80 at one time. After pollination, a few will set into round, green fruits that exhibit fine segmentation seams. Fruit take some months to mature. The outer exocarp will begin to split at the seams and drop the hard endocarp seed shells to the ground. These shells are thick and tough and are best roasted until they crack open, revealing the white kernel inside.

Figure 11. Flower buds on A. moluccanus. Sandy Corner Rest Stop, Ayr. © JPM, 2022.

Figure 12. Open flowers on A. moluccanus. Atlas of Living Australia. © M. Fagg, 2010.

Figure 13. Open flowers on A. rockinghamensis. Atlas of Living Australia. © Paluma, 2015.

Figure 14. Green nut on A. moluccanus. The segmentation seams are barely visible (one extends upwards from the tip of my thumb). Sandy Corner Rest Stop, Ayr. © JPM, 2022.

Figure 15. Nuts on A. rockinghamenis, clearly showing the segmentation seams. © Paluma, 2022.

Figure 16. Ripe nuts of A. moluccanus, bursting at the seams. Atlas of Living Australia. © K. Coleman, 2021.

Figure 17. Dried whole fruit, exocarp still intact. Acquired from Sandy Corner Rest Stop, Ayr. © JPM, 2022.

Figure 18. Endocarp shell after removing the dried exocarp. Acquired from Sandy Corner Rest Stop, Ayr. © JPM, 2022.

Figure 19. Kernel of a cracked shell, also conveniently demonstrating how thick the endocarp is. Oops! It's just cobwebs!! The developing kernel had been destroyed by some mould, or perhaps never fully developed because it was picked too early, straight from the tree. But I was only in Ayr on this day... oh well! Acquired from Sandy Corner Rest Stop, Ayr. © JPM, 2022.

Figure 20. Actual demonstration of the kernel. Atlas of Living Australia. © I. Mcmaster, 2010.

Culinary Uses

Candlenut has been used as a source of food and seed oil for millennia all across the Pacific, particularly in Malaysia, Indonesia, China, India, Philippines, Hawaii and other Pacific Islands. In its raw form it is toxic and should not be eaten; First Nation tribes of northern Queensland traditionally roasted the hard, inner shells on slow coals until they cracked, at which point they were cooled and eaten. Candlenuts are an excellent source of thiamine; Tim Low (Wild Food Plants, p.93) reports one Australian sample containing more than 4,000 μg (micrograms) of thiamine, a truly astounding amount.

Oil can be cold-pressed from the nuts and used in cooking, dressings and as fuel in oil lamps.

Figure 21. Candlenut kernels and cold-pressed oil. No affiliation. © laketoba.net, Indonesia.

Other Uses

In Hawaii and some other Pacific Islands, candlenut kernels were skewered onto sharpened palm fronds and burnt at important ceremonies. Each kernel can burn for approximately 10-15 minutes, and this became a measurement of time in many of these places.

Video: Candlenut candles. © Kelvin Surijan, 2015.

Caution!

Candlenut kernels are toxic raw. It should not be eaten unless it is first roasted to denature the poisonous substances. Sap from cut branches, stems or fruit can cause dermatitis and skin inflammation.

Aleurites as a genus has many close relatives of the wider Euphorbiaceae family. Many of these look-alikes are toxic raw and cooked, but their seed oils can have useful medicinal properties. Some of these genera include: Croton, which is prolific in Australia, has otherwise poisonous seeds but excellent medicinal sap used for skin healing; various species of Mallotus which are also very common in Australia with inedible hairy nuts on long beads; and the round-leaved Omphalea, mostly found on Cape York, also highly toxic. Some of these species were formerly classified as Aleurites but further research has diversified them from true candlenuts. None of these look-alike species exhibit the dual leaf-stem glands, or young leaf 'flour'. Some of their other features, such as leaf shape, fruit shape and flowers, are similar.

![Aleurites moluccanus [Nuts - Sandy Corner Rest Stop, Ayr, 2022] sml.jpg Aleurites moluccanus [Nuts - Sandy Corner Rest Stop, Ayr, 2022] sml.jpg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb4f94160-092a-43ff-bc11-3609d3d24ac8_1000x1333.jpeg)

![Aleurites rockinghamensis [trunk - ATLAS - Tim, 2021].jpeg Aleurites rockinghamensis [trunk - ATLAS - Tim, 2021].jpeg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fd0a614f2-f2a7-4e3d-82e9-abde449d7d98_1000x1333.jpeg)

![Aleurites rockinghamensis [trunk - ATLAS - R. Cumming, 2019].jpeg Aleurites rockinghamensis [trunk - ATLAS - R. Cumming, 2019].jpeg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0e9a0aa6-e9b1-4a2c-823a-d3b9d60d4df3_999x1457.jpeg)

![Aleurites moluccanus [trunk - ATLAS - M. Fagg, 2012].jpeg Aleurites moluccanus [trunk - ATLAS - M. Fagg, 2012].jpeg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb2cd5029-be8f-4f92-b450-1bae0b1384cc_562x750.jpeg)

![Aleurites moluccanus [Leaf - Sandy Corner Rest Stop, Ayr, 2022] sml.jpg Aleurites moluccanus [Leaf - Sandy Corner Rest Stop, Ayr, 2022] sml.jpg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F392726ce-e23b-43d0-88e6-14f498ac4299_1000x1333.jpeg)

![Aleurites rockinghamensis [leaf glands - ATLAS - S. Fitzgerald, 2022].jpeg Aleurites rockinghamensis [leaf glands - ATLAS - S. Fitzgerald, 2022].jpeg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fd407f5b9-ed64-450d-8b2b-c317f1d78f00_2048x1536.jpeg)

![Aleurites moluccana [young leaves - Wikipedia - Geographer, 2012].jpeg Aleurites moluccana [young leaves - Wikipedia - Geographer, 2012].jpeg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F69b35dd1-a8d6-46b2-89bc-d6c80627c777_1333x1000.jpeg)

![Aleurites moluccanus [young foliage - ATLAS - B. Shevaun, 2020].jpeg Aleurites moluccanus [young foliage - ATLAS - B. Shevaun, 2020].jpeg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F3a537943-69d1-4b4f-bfb4-43d8b17bd305_1536x2048.jpeg)

![Aleurites molucannus [foliage - ATLAS - R. Chapman, 2007].jpeg Aleurites molucannus [foliage - ATLAS - R. Chapman, 2007].jpeg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F5fc650d9-fca4-4ce4-80c3-4f45584d92df_500x375.jpeg)

![Aleurites fordii [foliage - ATLAS - G. Cocks, 2013].jpeg Aleurites fordii [foliage - ATLAS - G. Cocks, 2013].jpeg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb4a35a9d-bd52-45b5-89fd-046b0eb2d4da_1001x660.jpeg)

![Aleurites moluccanus [Flower buds - Sandy Corner Rest Stop, Ayr, 2022] sml.jpg Aleurites moluccanus [Flower buds - Sandy Corner Rest Stop, Ayr, 2022] sml.jpg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F64432233-d49d-41a0-a756-3a0637220908_1333x1000.jpeg)

![Aleurites moluccanus [flowers - ATLAS - M. Fagg, 2010].jpeg Aleurites moluccanus [flowers - ATLAS - M. Fagg, 2010].jpeg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F907c315d-f308-4ad3-8fec-d40b0926a4ad_749x498.jpeg)

![Aleurites rockinghamensis [flowers - ATLAS - Paluma, 2015].jpeg Aleurites rockinghamensis [flowers - ATLAS - Paluma, 2015].jpeg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa779a69b-91b1-499c-80ec-c15ffc25c952_2048x1536.jpeg)

![Aleurites moluccanus [Nut - Sandy Corner Rest Stop, Ayr, 2022] sml.jpg Aleurites moluccanus [Nut - Sandy Corner Rest Stop, Ayr, 2022] sml.jpg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F253b094a-e0c6-4001-b595-7a01a2f1297f_1211x1000.jpeg)

![Aleurites rockinghamensis [nuts - ATLAS - Paluma, 2022].jpeg Aleurites rockinghamensis [nuts - ATLAS - Paluma, 2022].jpeg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa3cdf6e3-a321-46a6-b96d-5b5070fe9f6a_2048x1536.jpeg)

![Aleurites moluccanus [nuts - ATLAS - K. Coleman, 2021].jpeg Aleurites moluccanus [nuts - ATLAS - K. Coleman, 2021].jpeg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F1429c730-8a82-430f-8bec-0ee899952508_2048x1536.jpeg)

![Aleurites moluccanus [dried fruit] 20221120_213750 sml.jpg Aleurites moluccanus [dried fruit] 20221120_213750 sml.jpg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa56d377b-f7d6-42f8-b57f-a05627c327b9_1310x1200.jpeg)

![Aleurites moluccanus [nut] 20221120_213854 sml.jpg Aleurites moluccanus [nut] 20221120_213854 sml.jpg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F4b548a70-70ab-4e20-9058-f2f701bdb8a5_1200x1230.jpeg)

![Aleurites moluccanus [kernel - cobwebs!]20221120_214611 sml.jpg Aleurites moluccanus [kernel - cobwebs!]20221120_214611 sml.jpg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F1715692d-7040-4cb1-ad2a-c8c08a78ccb9_1100x1214.jpeg)

![Aleurites moluccanus [kernel - ATLAS - I. Mcmaster, 2010].jpeg Aleurites moluccanus [kernel - ATLAS - I. Mcmaster, 2010].jpeg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9c007582-88ca-425d-9b65-833fe8b92e73_1620x1080.jpeg)