Edible Nectars: Grevillea, Banksia & Eucalyptus

Grevillea species, Banksia species, Eucalyptus species & Corymbia species.

Grevillea banksii in full bloom. Newington, Sydney. © JPM, 2022.

Ever had that sudden craving for sugar but you ran out of candy? It just turns out that Australia is home to some of the sweetest natural confectioneries growing free in backyards and wilderness areas across the continent.

Names

As this entry concerns three different plant families, Grevillea (G.), Banksia (B.) and Eucalyptus (E.), specifics regarding identification, excepting eucalyptus, which I expect anyone living in Australia to identify without effort, will be supplied in the figures below. However, there are several specific species worth mentioning by name for the intrepid bush food collector or interested home gardener.

For the grevilleas, the northern G. pteridifolia or "Golden Grevillea" is now an extremely common ornamental in gardens around the country (and occasionally overseas) and a prolific producer of edible nectar. It may still be found in abundance in its native habitat across the Top End from Broome in Western Australia, across the Northern Territory and on to Cape York and Cairns. On the eastern and south-eastern coast the enormous G. robusta, otherwise known as the silky oak or silver oak (and not to be confused by name with the native she-oak, Casurina, which looks like a pine tree), puts on its show of nectar-laden golden flowers every year, as does the cream or red-flowered G. banksii. In the arid regions of the interior, one may find the delicious G. juncifolia and G. eriostachya, among many other grevillea species which all have edible flower nectar.

Of the banksias, B. integrifolia's thick, candle-like cream-yellow flowers is very abundant on the majority of the east coast. The swamp banskia, B. dentata, is the only variety to be found regularly in the north western parts from Broome across to the Kimberleys and Kakadu. South western Australia's wheat belt region is home to at least 58 of Australia's 173 identified species alone! All banksias flowers have edible nectars, but in my experience significantly lag behind grevilleas in their overall nectar output and really require soaking in water to extract their sweetness.

Eucalyptus is probably Australia's most iconic tree (I would rank it just ahead of the wattle) due to its prominent association with koalas, drop bears and the medicinal throat lozenge "eucalyptus drops" and antibacterial eucalyptus oil. While eucalyptus trees were often far more important to the native tribes for their supply of edible lerps (see figure 15 below), galls (see figure 19 in the previous article on acacias; similar galls can occur on eucalyptus flowers), "sugar bag" (native beehives) and nesting birds and marsupials, virtually all eucalyptus varieties produce copious amounts of edible nectar. Of note are the bloodwoods, E. intermedia, well known for their blood-red sap and nectar-bearing flowers, and the Tasmanian "cider gum", E. gunnii, noted for its allegedly maple-syrup flavoured sap. The large-flowered ironbarks and Corymbia ficifolia (formerly E. ficifolia) likewise have abundant harvests of nectar available for the intrepid adventurer-survivalist.

Habitat and Range

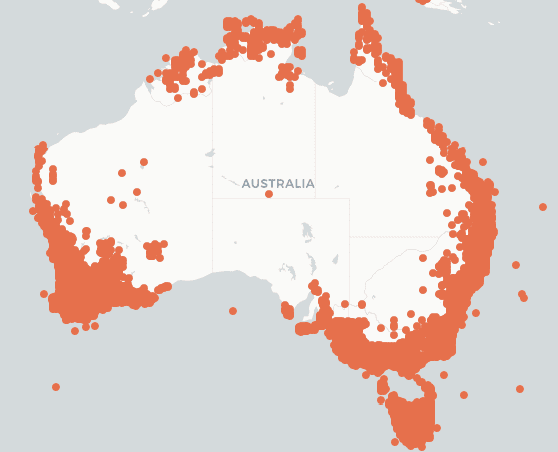

Excepting the very harshest desert or saltpan regions, grevillea, banksia and eucalyptus can be found across the continent, and some species have even become invasive pests in other places of the world after careless introduction. Banksias are abundant in Australia's loamy, infertile soils, especially in heath or dry woodland, although they are less common in the wet north, alpine and in the red centre regions. Grevilleas are a little more hardy, being also found at altitude and throughout desert climes. There is a eucalyptus for almost every acre of Australia, deserts, swamps and snowy alpine regions included.

Figure 1. Distribution of Eucalyptus (all species) across the continent. Atlas of Living Australia.

Figure 2. Distribution of Grevillea (all species) across the continent. Atlas of Living Australia.

Figure 3. Distribution of Banksia (all species) across the continent. Atlas of Living Australia.

Grevillea, banksia and eucalyptus flower all year round, especially after rain, but more prolifically in spring and late summer (especially for the eucalypts). They make excellent ornamentals and are best suited to Australia's generally terrible soil, although it is important not to fertilise them with high phosphorus fertilisers (e.g. chicken manure) as this can kill the plants outright (especially banksias).

Identification

Grevillea and banksia can both be identified for their tough and colourful flower spikes. Ranging from whites, creams to golden orange, reds and rarely purple and green, they flower all year round with prolific flowering in the spring or after rainfall. Differences between grevillea and banksia rest mostly in the shape and colour of the leaves (especially the undersides), the overall shape of the flower spikes, and the shape of the seed cones/pods.

Figure 4. Leaf variation in four species of banksia, from the left: B. serrata, B. oblongifolia, B. marginata, B. ericifolia. Many common species of banksia have white undersides on their leaves, and serrated edges. Wikimedia commons.

Figure 5. Banksia marginata flower. Left, immature (no nectar). Right, mature (nectar-bearing). Banksia flowers are always conical or tubular, like fat candles. Note the white undersides on the leaves. Wikimedia commons.

Figure 6. Spent banksia cone. The open pods have already released their seeds and may remain on the tree for years afterwards, a key identifying feature. Again, note the white undersides of the leaves. Wikimedia commons.

Figure 7. Unspent banksia cone. Notice that the pods are closed, indicating the seeds are still inside. Dharawal National Park. © JPM, 2022.

Figure 8. Golden grevillea, G. pteridifolia, flowers and foliage. Unlike tubular banksias above, grevilleas spike their flower anthers usually on one side of the supporting stem and their leaves do not have white undersides, but may have white fuzz/fine hairs. Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 9. Cream coloured G. banksii flower. The nectar pools in pockets near the stem, at the base of each anther. Pollen is visible on the anther tips. Narabeen Lagoon, NSW. © JPM, 2022.

Figure 10. G. banksii with young seed pods (foreground; immature flower in the background). Pods will turn brown but remain unopened when seeds are ripe. Note the white fuzz on the underside of the leaf, contrasted to banksia which would be completely white. Wikimedia commons.

Figure 11. G. robusta in full flower (also header image at top of this article). Note the opened, spent seed pods (brown) which do not look like banksia cones. Wikimedia commons.

Figure 12. G. decurrens, otherwise known as the fuschia grevillea. It is known to have edible seeds. Wikimedia commons.

Figure 13. Edible seeds of G. decurrens, removed from their pods. © Gary Fox. Territorynativeplants.com.au

Figure 14. Corymbia ficifolia, formerly Eucalyptus ficifolia, one of the largest flowering gumnuts one can find in Australia. If you look close enough, you can see the glistening nectar on the yellow "cup" of the flower, a favourite of possums, sugar-gliders, lorikeets, bees and bush foodies across the country. This nectar regenerates every day until the flowers set into gumnuts, or for approximately 24 hours if the flowers are cut off the tree but the stem is kept in a vase of water. All eucalyptus flowers have the same shape; only size and colour will change.

Culinary Uses

Viable species will drip a sticky, sweet liquid from mature and fully opened flowers which tastes, depending on the variety, like mild honey to a quite strong sugar syrup. For grevilleas and banksias and large eucalyptus flowers, nectar can be extracted directly from the base of the flowers with the brush of a finger by pushing in deep along the flower's stem, or, if you're particularly keen to brave the countless bugs, ants and bees that simply love these flowers, the lips. All grevillea, banksia and eucalyptus flowers may be removed from plants and dipped into water, infusing it with their delightful sweetness, a favourite sweet treat of many native Australian tribes, especially in the arid interior and Top End. This method is especially pertinent for small eucalyptus flowers as their "cups" can often be too small to fit a human finger or tongue. Simply cut the cluster and soak in water to release their sweet nectar (optional - sieve the bugs out of it as well). Flowers will regenerate nectar daily until they set their pods. Nectar is best harvested in the early morning before the lorikeets get into it.

Video: Harvesting desert grevillea for dessert with Malcolm Douglas and the tribes of the arid interior, 1979. © Malcolm Douglas.

Seeds of both grevillea and banksia may be ground into flour as an emergency food. Due to difficulties extracting enough seed from banksia cones or grevillea pods, I have been unable to ascertain palatability or toxin levels of these products and they are probably best kept for absolute emergency food situations, with G. decurrens (figures 12-13 above) as a notable exception. It is said that exposing ripe but closed banksia cones and grevillea pods to fire or heat (e.g. an oven) will cause them to open and release their seeds for human use. Otherwise the cones and pods can be left to sun dry and this will cause them to open in due time. Note that the seeds of these plants are designed to spread by wind dispersion and they have wings to aid this, similar to maple seeds (figure 13 above).

The Tasmanian cider gum, E. gunni, has edible sap, akin to a light maple syrup. The sap can be acquired by slashing the inner bark with a knife or axe, or tapping the tree with a drill and pipe akin to maple syrup harvesting. The tribal people of Tasmania used to ferment this sap into an alcoholic beverage, hence the name "cider gum". Other eucalyptus saps may have edible properties but are mostly unresearched so caution is advised if you wish to try them; Tim Low (p.153) cites E. viminalis and E. mannifera as examples of other edible eucalyptus gums, especially if the liquid sap is left to dry into the delicious sweet the settlers called "manna". Bloodwood sap may be used as a topical antibiotic but should not be taken internally.

All Eucalyptus trees will be home to lerps, the conical, sugary excrement of the psyillid bug. Gently scrape the lerps from the leaf and eat; the bug will be a tiny red dot which may or may not remain stuck in the sugary cone - dissolving the sugary lerp in water will cause the bug to float on the surface where they can be skimmed off, if you find the idea of eating a bug the size of a full-stop to be repulsive. This food was highly prized by tribal peoples across the continent, and was sometimes collected by the bagful for special ceremonies and trading.

Figure 15. Edible, sugary lerps on eucalyptus leaves. Yes, the thought of eating bug poop-sugar is gross, but you already eat bee vomit (honey) without complaint so what's the problem?

Medicinal Uses

Eucalyptus leaves may be steam-distilled to extract their well-known essential oils. The species E. globulus is the main one used for commercial production. It is important not to take eucalyptus leaf oils internally except in minute amounts due to potentially severe complications from their toxicity. Eucalyptus oils exhibit strong antibacterial action when applied topically, and breathing in the mist from adding eucalyptus oil to steaming water is a well-known tonic for chesty coughs and other cold and flu-like illnesses.

Caution

Some grevilleas, especially the gigantic G. robusta, are known to have extremely irritating bark sap. Skin and eye contact should be avoided from touching grevillea sap oozing from bark or broken flower stems. Some eucalyptus saps/gums and all eucalyptus essential oils derived from the leaf are also quite toxic internally. Always seek advice from specialists in Australian homeopathy, naturopathy and traditional herbal medicine before using or consuming any eucalyptus product.

A final caution remains regarding the flammability of eucalyptus essential oils, including in the living trees themselves. This is the reason Australian bushfires are so bad; the trees literally harbour a potentially explosive, flammable oil!

![Grevillea banksii [Tree - Newington, NSW] sml.jpg Grevillea banksii [Tree - Newington, NSW] sml.jpg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Dp1a!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F75ff2478-3fdd-48b2-944b-b359818a47ec_1333x1000.jpeg)

![Banksia [foliage L to R B. serrata, oblongifolia, marginata, ericifolia wikicommons].jpg Banksia [foliage L to R B. serrata, oblongifolia, marginata, ericifolia wikicommons].jpg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!k2gk!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F5fd9f191-c0ce-4bda-9cf2-dc475847adc0_640x360.jpeg)

![Banksia marginata [immature and mature flowers wikicommons].jpg Banksia marginata [immature and mature flowers wikicommons].jpg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!rC0M!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fdb00a90e-99d2-4fe8-ad39-3608b16b698e_640x458.jpeg)

![Banksia integrifolia [seed pod discharged wikicommons].jpg Banksia integrifolia [seed pod discharged wikicommons].jpg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!A4IZ!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ff0613fd4-7f72-4ff2-9b0a-a7516c7a61ed_640x853.jpeg)

![Banksia [cone] 20220604_113608 sml.jpg Banksia [cone] 20220604_113608 sml.jpg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!KA16!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe7a0fd6f-f9ce-4f83-8b06-13cd1805ff0e_1333x1000.jpeg)

![Grevillea pteridifolia [Foliage and Flowers wikicommons].jpg Grevillea pteridifolia [Foliage and Flowers wikicommons].jpg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Q70m!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F642a07d6-a7e2-4a42-8c8f-f6aadce20650_640x480.jpeg)

![Grevillea banksii [flower, Narabeen Lagoon NSW sm].jpg Grevillea banksii [flower, Narabeen Lagoon NSW sm].jpg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!-iVb!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa14595bf-f227-4be7-b5e0-f21c381ef256_1800x1350.jpeg)

![Grevillea banksii [pods forming wikicommons].jpg Grevillea banksii [pods forming wikicommons].jpg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!V8lH!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0e78bac5-f16f-4aa8-a930-b297f504578e_640x853.jpeg)

![Grevillea robusta [flowers & pods wikicommons].jpg Grevillea robusta [flowers & pods wikicommons].jpg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!kfuL!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F412eafc1-8056-4614-9828-4d24dccabd69_640x480.jpeg)

![Grevillea decurrens [flower and foliage wikicommons].jpg Grevillea decurrens [flower and foliage wikicommons].jpg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!qOP2!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fac44c746-741d-4dd5-81cd-2b42d749cddb_640x427.jpeg)

![Grevillea decurrens [edible seeds - Gary Fox].jpg Grevillea decurrens [edible seeds - Gary Fox].jpg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!K-85!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F6c07a1b9-bd14-403f-86cf-18d473d062c1_500x359.jpeg)

![Corymbia ficifolia [flowers, formerly Eucalyptus f. wikicommons].jpg Corymbia ficifolia [flowers, formerly Eucalyptus f. wikicommons].jpg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!HeSv!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0e9acf65-f8b7-4c0c-af63-a6fcd1d41e1f_640x425.jpeg)

![Eucalyptus lerp [wikicommons].jpg Eucalyptus lerp [wikicommons].jpg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!z_9x!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F87db1159-2a61-4960-9699-d72cf9221ff1_800x450.jpeg)